As Japan tries to reopen its borders amid the seventh wave of coronavirus infections, visitors from abroad may find themselves not only covering up with face masks but covering their tattoos as well. People from overseas may find it surprising that tattoos are still largely taboo in Japan, but there is a long history of inking skin that is a fundamental part of social attitudes toward tattoos.

-

01

A rich medieval history

While inked foreigners are not judged as harshly as Japanese, there is still a stigma attached to tattoos. It’s not uncommon to find signs at public bathhouses banning people with tattoos or requiring them to be covered up. There are skin-colored adhesive patches on the market for that, but inked onsen users can also cover up with clothing, as the All Blacks rugby team has done in Japan.

The main reason for the ban is that tattoos, known as irezumi in Japanese, have long been associated with criminal gangs, or yakuza. In the postwar era, a government movement to mobilize businesses to stop all dealings with gangs led bathhouses and other establishments to display signs or stickers banning yakuza and, by extension, people with tattoos.Understanding irezumi involves a deeper look into its history. A 3rd-century account from China remarked that Japanese used tattoos to indicate social class and protect themselves from harmful sea creatures. In the Edo period (1603–1867), express couriers, firemen and steeplejacks are said to have tattooed themselves to adorn their skin, which was often bare to facilitate movement in their physically demanding jobs. Such tattoos were often a source of pride for the bearers and their community. They evolved a demand for elaborate, artistic tattoos with protective qualities, such as dragons, which were thought to bring rain. The full-body tattoo, and the irezumi artist, were natural evolutions of this trend.

![Examples of full body tattoos from Japan during the Edo period

Baron Raimund von Stillfried, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]()

Examples of full body tattoos from Japan during the Edo period Baron Raimund von Stillfried, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Woodblock print artists also depicted tattooed heroic outlaws from the kabuki stage and popular romances who helped the oppressed amid great social injustice. Writers later took up this idealization. There have been many stories, and modern TV dramas, celebrating the cherry blossom shoulder tattoo worn by the fictional character Toyama no Kin-san. Based on the real-life samurai official Toyama Kagemoto (1793–1855), Toyama is a magistrate in disguise who aids commoners. When revealing himself as a judge to malefactors, he flashes his tattoo and utters his catchphrase: “Do you not see this blizzard of cherry blossoms?”

![Woodblock prints depicting characters with tattooed bodies

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]()

Woodblock prints depicting characters with tattooed bodies Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

-

02

Criminal elements

In reality, it was unusual for the elite, including samurai, to sport irezumi. Furthermore, from 1720, law-enforcement officials began branding criminals with tattoos on their foreheads or arms. This stigma was dramatically strengthened in 1872. The Meiji government was trying to modernize Japan after two centuries of international seclusion and was keen not to offend foreign mores with displays of virtual nudity in public, which was seen among some irezumi enthusiasts. It banned decorative irezumi, driving the practice underground.

The ban ended in the U.S. Occupation (1945–1952) but it had a lasting social impact. The public continued to associate irezumi with criminality, especially yakuza, who endure painful, expensive and long-term body-inking sessions in the traditional tebori technique. Rather than indicating affiliation to a gang, yakuza are inked to express an important personal symbol or story. For instance, a tattoo of a carp swimming upstream can convey fortitude. It’s one of many stock irezumi images including natural, mythological, literary or religious creatures or entities. Ironically, these elaborate artworks are usually covered up in everyday life.

![A Japanese irezumi tattoo artist works on a client at an overseas event

Mykola Romanovskyy/Shutterstock.com]()

A Japanese irezumi tattoo artist works on a client at an overseas event Mykola Romanovskyy/Shutterstock.com

“Tattoo culture in Japan is still a taboo, but that’s why the culture is beautiful,” renowned tattoo artisan Horiyoshi III told Vice . “Fireflies can only be seen at night because their beauty is only visible at night. They aren't appreciated in daylight. When something becomes a fashion, it isn’t fascinating anymore.”

-

03

Rediscovering Ainu and Ryukyu traditions

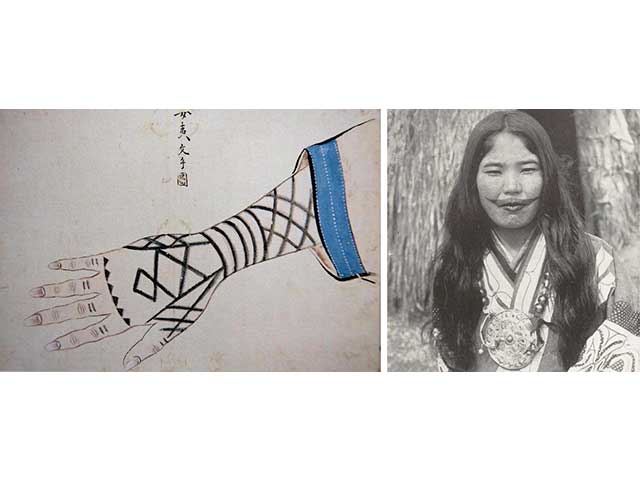

Tattooing is a tradition of the Ainu and Ryukyu peoples in northern and southern Japan. Ainu women wore tattoos, called shinue or panai, around their mouths and on their hands. People in the Ryukyu archipelago had different tattoos, called hajichi, depending on their island. The Meiji ban affected these communities as well. But a revival has been taking place as younger generations rediscover these art forms through museum exhibits, social media and other means. Some are embracing them to affirm their sense of identity.

![Left: Example of Ainu tattoo design for the hand

Right: An Ainu woman with a face tattoo that surrounds her mouth and covers her lips

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

アイヌカムイ, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons]()

Left: Example of Ainu tattoo design for the hand Right: An Ainu woman with a face tattoo that surrounds her mouth and covers her lips Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons アイヌカムイ, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

“I felt very happy to be described as beautiful in my Ainu kimono and shinue, as I have never been told that I looked beautiful,” Mayunkiki, an Ainu artist and musician, said in a 2020 speech to the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation. “And that is when I truly wished to become a beautiful Ainu woman.”

"When I got it done, it just felt so great and it just all felt so natural to me," Akemi Matsuzaki, an Okinawan native, told The Washington Post . "Though I was born in Okinawa and am working here, getting hajichi made me feel even more strongly of the fact that I really am here, and I feel more comfortable and proud of who I am."

READ MORE- Visiting Japan with Tattoos: Manners/Etiquette

-

![]()

- Need to Know

The Tokyo Station Hotel

1-9-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo

Go here

Go here